About

The Office of Foundation Oversight

The OFO is a joint Congressional and civilian initiative designed to strengthen nonprofit oversight through nonpartisan investigations into corruption, fraud, and conflicts of interest. Since its inception in 2017, the Office has investigated 21nonprofits nationwide.

-

Six were permanently closed.

-

Seven lost their 501(c)(3) status and fined.

-

Sixteen were referred for suspension and debarment from future grants.

-

Four CEOs were terminated along with six CFOs who also had their CPA licenses suspended or revoked.

-

Numerous Board members were removed.

-

Over one million dollars was returned.

-

Six individuals were referred for federal prosecution.

-

Four nonprofits were cleared of all wrongdoing.

-

Several investigations are ongoing.

Many of these cases were uncovered thanks to tips from everyday citizens, proving that one person can truly make a difference.

In the past decade, violations committed by nonprofit insiders have reached unprecedented levels, with most going unreported and unpunished. By exposing both the perpetrators and those complicit in concealing their actions, we aim to make it clear: abuse of trust will not be tolerated, and there will be serious consequences.

The Office of Foundation Oversight is no ordinary watchdog group; we serve as the eyes and ears of the United States government, protecting the interests of the American people. Through independent investigations into corruption, misconduct, and conflicts of interest, we work to create a more accountable and ethical nonprofit sector. Partnering with IRS Criminal Investigations, the Office of the Inspector General, and Department of Homeland Security's General Counsel, we form a coalition dedicated to delivering justice to those who betray public trust. As a key participant in Suspension and Debarment Programs, we are committed to referring organizations implicated in mismanagement and abuse of federal grant funds. We also collaborate with state legislators to advocate for stronger penalties in cases of fund misappropriation intended to assist the disadvantaged. Additionally, we will continue pushing for tougher consequences for individuals complicit in concealing such crimes and demanding full transparency from nonprofits in their financial operations. Noncompliant organizations risk losing their nonprofit status and future access to federal grants.

Facts about

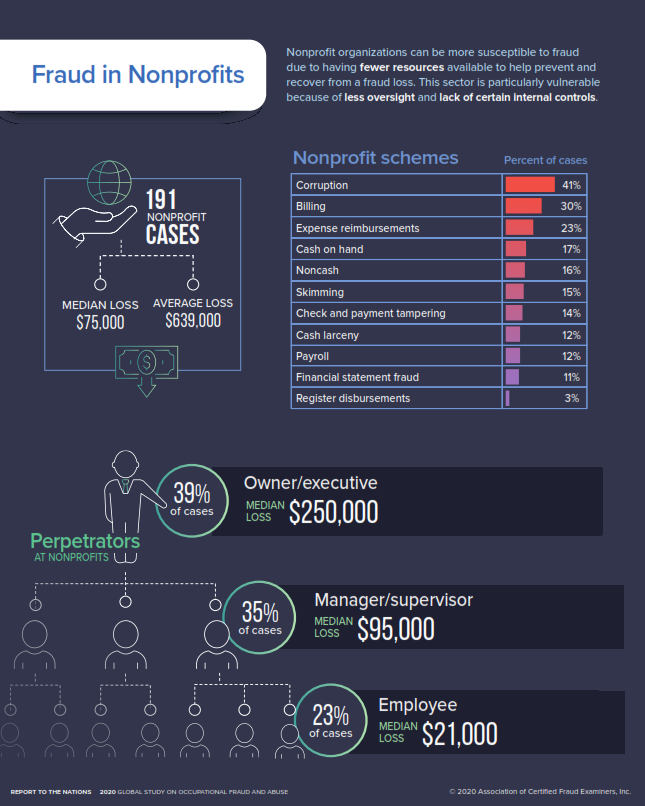

Nonprofit Fraud

It is important to understand the types of fraud your nonprofit organization is most likely to experience in order to create effective anti-fraud policies. The Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse, the definitive study by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), provides the following data:

The mission of nonprofit organizations is generally philanthropic, and employees, especially senior management, share this mission. Nonprofits are therefore more trusting of their employees and have less strict financial controls than for-profit organizations. As a result, nonprofit embezzlement cases and other forms of employee fraud are on the rise.

Several noteworthy trends in occupational fraud are highlighted in the ACFE study, as well as how companies can combat the problem internally.

Important trends emerged from the 2,400 or so fraud cases studied. According to the ACFE, all fraud schemes can be categorized according to these patterns and classified into three categories: misappropriation of assets, corruption, and financial statement fraud.

DID YOU KNOW theft of funds is not generally covered by insurance? The employee dishonesty provisions of a standard insurance policy does not protect a charity from loss when an employee conducts an unauthorized fund-raising campaign and uses the proceeds for himself, according to the First Circuit Court of Appeals. The Court affirmed a District Court decision denying coverage for the Special Olympics International and its Massachusetts affiliate. In that case, an area manager hired a telemarketer to launch a fund raising campaign using the Special Olympics name and logo without the organization's knowledge. He deposited the raised funds in an unauthorized bank account opened in the organizations name from which he wrote checks to himself totaling over one million dollars. When this was ultimately discovered, as it usually is, Special Olympics sought to recover those funds under their employee fidelity policy. Not only did they not recover a single dollar, they lost even more by way of legal fees, payroll dollars, and undetermined donations withheld from benefactors whose confidence was now lost.

Insurance policies are intentionally ambiguous, so it is up to the insured to read and understand the fine print. A simple re-wording of a clause can change the entire meaning, so if it's not transparently clear, have them reword it. Remember: Insurance Companies are not in business to pay out claims. An Executive over a federally funded and/or charitable trust has the fiduciary responsibility to read every page, every provision and every clause, no matter how time consuming and boring it may be, and not sign anything that is not fully understood. Asking for additional clarification does not make one look foolish or ignorant, quite the opposite.

How to Prevent Nonprofit Fraud

To help combat fraud, we recommend following these basic steps:

-

Keep it locked up! This includes cash and checks. When counting money, make sure more than one person is present.

-

Implement a strict "separation of duties" policy. Different staff should handle cash functions such as deposits, check writing, and bank reconciliations.

-

It is imperative to keep bank reconciliations up-to-date. It may be necessary to hire temporary help to bring your bank reconciliations up to date if you're behind.

-

Checks should not be pre-signed. Safeguards need to be in place if autopen signatures are used.

-

You shouldn't be too trusting! Sometimes it is the people you expect the least that do the most damage.

Last but not least, monitor the cash balances in your fund accounting software, send alerts to more than one supervisor, and keep track of your audit trails. Put policies in place and ensure they are enforced. Nonprofit fraud is easier to prevent than to detect, but if you need to file a report, contact your local law enforcement agency. If that does not yield the results you expect, contact The Office of Foundation Oversight for more useful information.

Resources

Nonprofits In The News

WHAT IS OVERSIGHT?

Oversight serves as a critical governance tool to ensure that organizations, groups, and governments operate legally, ethically, and in alignment with their stated mission. While each nonprofit’s Board of Directors holds the primary responsibility for overseeing the organization, this internal oversight is not always sufficient. Legally, nonprofit boards are expected to exercise the same level of care as an ordinarily prudent person in managing the organization’s finances and compliance with laws. However, it has been demonstrated that board members often fail in this duty, sometimes committing or enabling violations of federal and state laws, as well as their own charter bylaws. This negligence extends to concealing crimes that occur under their watch. Even when boards justify these cover-ups with good intentions, they are still committing illegal acts. The situation becomes more severe when these organizations solicit financial contributions under the guise of being moral, ethical, and financially responsible.

For nonprofit oversight to be truly effective, it must be conducted by an impartial third party with no ties to the organization. The purpose of External Oversight is to hold Internal Oversight accountable. Just as government agencies are subject to external oversight, nonprofits and their boards should be equally accountable, particularly when funded by public donations or government grants.

REPORTING FRAUD

"The Office of Foundation Oversight provides a confidential assessment of your situation to help determine the best course of action, whether by phone, email, or personal consultation. All services, advice, and actions are offered free of charge. We do not accept charitable donations or federal grants; instead, our work is supported by dedicated volunteers who uphold the timeless values of truth and justice."

Contact Us

If you suspect fraud within a nonprofit and need assistance, we’re here to help.

602-577-1679

Special Appreciation to our partners